A Crowd-sourced Ventilator: It’s not possible... is it?

Kellogg Fellow Rob Collins has been teaching on the MSc in Software Engineering at the University of Oxford for the last 10 years. In this blog he describes how he was motivated to set up the Ventilator Crowd project, and use his skills as a Systems Engineer to help in the fight against Coronavirus.

On the evening of 15 March this year, my brother sent me an e-mail. It was not so remarkable I suppose, that I received his e-mail in the same moment that I clicked on the send button of an e-mail to him. What was more unusual, is that the wording of his e-mail and mine were almost identical. His e-mail read as follows:

Rob,

The country needs Ventilators.

If there were a standard, simplified design we could perhaps get everybody with a 3D printer to start making components.

Components could then be sent to assembly plants.

Consider it an effort like Dunkirk, but for engineers.

What do you think?

An intriguing idea. Could it be possible to somehow organise an army of engineers, builders, makers, crafts-people and enthusiasts to build a safety-critical, medical device? The simple answer to that question, by any rational judgment would have to be “almost certainly not”.

On that evening I felt genuinely scared. Worse, I felt powerless and dejected. And so I launched the Ventilator Crowd project primarily, of course, to try to do something useful. But I also did it because I decided that if that evil little virus was going to get me I’d rather it got me whilst I, and others, were trying to fight back. I could not face the thought of any friend of family member coming to harm for the lack of technology that maybe I could help build.

My profession is not something as useful in these times as being a medic, or a virologist or an immunologist or an epidemiologist. But I guess that you have to do what you can do – I am a Systems Engineer by trade and training – and what we do is build complex machines. The headline ‘exam question’ for the Systems Engineering course I teach out of Continuing Education is “How do you get 1000 people to build a machine that is so complex that no individual understands the entirety of how it works” (and you may be surprised to consider that I count among those things modern jet-airliners and space vehicles for example). The headline question for the course on Safety Critical Software I teach as part of the MSc in Software Engineering is related, “How do you build a complex machine that has a low probability of injuring its users”. Both of those questions are highly relevant in this circumstance.

Overnight on 15/16 March I built and launched the Ventilator Crowd website. This was the public face of the project. In addition I set up a ‘Slack’ website – a powerful Internet tool used for collaborative projects. Slack enables asynchronous conversations by team members as well as allowing upload of drawings, videos, photographs and software models.

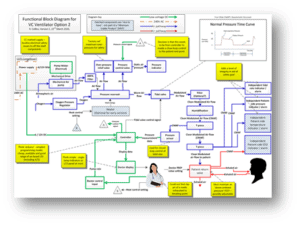

A technical diagram from the systems development

Within a few days I was swamped by volunteers from all over the world who wanted to join the project. We had core members from the UK, the US, India, Czech Republic and Norway, and I had teleconferences with other teams in South Africa, US, Italy and Brazil. By the end of the next week various designs were starting to come together. We drew in people with medical expertise who were able to understand the required functions and issues. We drew in mechanics, software engineers, and electronics experts. Things started buzzing with collaborative energy in a way that I have never before experienced on a traditional engineering project. It was an amazing and empowering feeling.

It very quickly became apparent that we were not the only people with the ‘collaboration’ and ‘rapid manufacture’ ideas. We learnt of dozens of projects throughout the world who were doing essentially the same thing. What’s more – they were generally sharing their information openly and encouraging use of ‘Intellectual Property’. How different this was to the world of secrets I have often lived in!

We were initially excited when we read news reports that the government had published “blueprints” (i.e. designs) for the devices that were needed. Surely this would prove to be a huge boost? What was actually published by the MHRA was an exceptionally poorly written set of ‘requirements’. I teach ‘requirements writing’ on both my Systems Engineering and Safety Critical Systems courses. Rest assured that none of my students would receive a passing grade for a document of comparable quality. We offered our support to MHRA– but were rebuffed. Disappointing.

The crowd-sourced machines were never intended to be ‘Plan A’. Of course, by far the best option was always going to be for expert medical engineering companies to rapidly ramp up their production. ‘Plan B’ would be non-medical engineering companies building simplified devices (Tesla had a great project for example). But we have not been ashamed to be ‘Plan C’ – developers of a ‘just good enough’, emergency, stop-gap solution that would only ever be used in a time of desperation.

In the event, and thus far, UK resources at least, have not been swamped past capacity. Great medical engineering companies have stepped up their production and for now the situation has stabilised.

In the mean-time I have learnt more than I ever really wanted to know about ventilation. Maybe more importantly, I have learnt that it is possible, using the modern tools of on-line collaboration to rapidly form a community to build something that reasonable people thought we could not.

My learning from this experience will probably end up as a research paper or a short-course at some point. But I leave you with my key learning: If you are feeling scared, powerless and despondent then muster your will-power to give something a try. Even if it is a bit crazy and smart people say it won’t work – you may be positively surprised. Like me, your morale may be restored.

Video of an early prototype of the electronic controller for our Ventilator can be found here:

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Kellogg College or the University of Oxford.